The mediator should be outcome-focused

He or she steers the process; through posing solution-focused questions, he or she encourages the clients to look ahead to their desired future situation and how they can achieve this outcome. It revolves around the outcome that the clients want to achieve. Solution-focused mediators will ask “What would you prefer instead of the conflict?”, defined in positive, realistic and concrete terms.

What practitioners say

Be aware of different mediation providers. Many formal and informal justice providers, such as police and cultural leaders offer mediation services. Some of them are not trained mediators. There are specialized and trained mediators available, to whom can be referred to.

Be aware of different mediation types. The main types of mediation are transformative, facilitative, and evaluative.

- Evaluative mediation is the style of mediation where the mediator exerts the most control throughout the mediation, and is the most vocal about the positions and offers of the parties.

- In facilitative mediation, the mediator will control the procedure of the mediation, but the parties control the outcome.

- Transformative mediation seeks to transform the conflict by empowering the parties to agree. The transformative mediator is only in the room to call attention to the needs, interests, values and points of view of the parties.

Be aware of the costs of mediation. When parties decide to mediate, the parties need to pay. In government-initiated mediation, the parties do not directly have to pay. Parties do not have to pay the police for reporting and offered mediation.

Conduct gender and power analyses. The dynamics in families will need to be identified. Power imbalance refers to decision-making and access to resources within a family. Who provides income? Who takes care of the children? Be careful, bringing up the topic of power balance can escalate the conflict. Moderate the words, use a different term than balance (for example: position of the parties, or personal standing of the parties). Economic status does not always defines power. Rather discuss negotiation ability

.

Resources and Methodology

- Most plausible interventions

- PICO question

- Search strategy

- Assessment and grading of evidence

- Recommendation

The three main sources used for this particular subject are:

Matthew R. Sanders, W. Kim Halford and Brett C. Behrens, Parental Divorce and Premarital Couple Communication (1999) Tamara D. Afifi, Tara McManus, Susan Hutchinson and Birgitta Baker, Inappropriate Parental Divorce Disclosures, the Factors that Prompt them, and their Impact on Parents’ and Adolescents’ Well-Being (2007) Paul Schrodt and Tamara D. Afifi, Communication Processes that Predict Young Adults’ Feelings of Being Caught and their Associations with Mental Health and Family Satisfaction (2007)

The article by Sanders, Halford and Behrens is based on a detailed observational analysis of couples’ interaction. The article by Afifi, McManus, Hutchinson and Baker bases its findings mostly on clinical and empirical evidence. The article by Schrodt and Afifi uses both empirical and meta-analysis to support its findings. According to the HiiL Methodology: Assessment of Evidence and Recommendations, the strength of this evidence is classified as ‘low’ to ‘moderate’.

Desirable outcomes

It is important to note that, based on uncertainty reduction theory, children need some information about the separation in order to reduce their uncertainty about the state of their family (Afifi, McManus, p. 80).

Undesirable outcomesResearch has shown that parents’ inappropriate disclosures give children psychological distress, physical ailments and feelings of being caught between their parents (Afifi, McManus, p. 79). Examples of inappropriate information are: negative information about the other parent (including complaints on lack of child-support), sensitive information and information judged not to be suitable (such as on financial issues, the reason for separation and personal concerns of the parent), and information that makes children feel caught between their parents (Schrodt, p. 209).

If children are completely uninformed about the separation, they can feel deceived, which can produce mistrust, diminished satisfaction with their parental communication, and a fear of establishing committed romantic relationships upon maturity (Afifi, McManus, p. 80). It can be difficult to for some parents to determine the fine line between disclosing the right amount of information and inappropriate information.

Balance of outcomes

In determining whether actively limiting disclosure of information to children about the other parent is more effective than sharing all information for their well-being, the desirable and undesirable outcomes of both interventions must be considered. The available literature suggests that certain information is not to be disclosed for the sake of the wellbeing of the child. In particular, revealing negative information about one parent would have severe negative effect physically and psychologically in both the long and short term. This type of information is classified as ‘inappropriate’. However, it is important to keep in mind that children should be informed during the separation process.

RecommendationIn light of the undesired outcomes of revealing inappropriate information to children, we make the following recommendation: For the well-being of children, it is appropriate that parents disclose information on the separation, albeit in a considered and limited way.

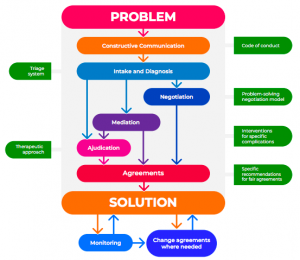

Apply the problem-solving approach

For a practitioner, it can be difficult to encourage families to work together and find solutions. Family conflicts often lead to tense and emotional situations. But there are effective methods to reach agreements.

The problem-solving approach focuses on finding solutions for the parties’ underlying needs and objectives. The first step for the parties and their helpers is to assess these needs and objectives. Then, the most appropriate interventions are identified, followed by negotiation. Remaining issues are solved by mediation, and if necessary, by adjudication. Compliance and effectiveness of the agreed upon solutions are monitored.

International research shows that taking the problem-solving approach contributes to reaching fair solutions.

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

Work towards building agreements based on shared understandings. All family members and their helpers should feel a shared responsibility to focus on finding a solution together.

Listen to needs of the other person. Parties should try to listen to and understand the other person. They should ask questions if there is unclarity about what the other person needs. When responding, parties should try to contribute to a solution and not just focus on the problem.

Identify the needs of each family member. What does each family member need in order to be able to move on?

Actively listen to what is being said. As a party, be an attentive and active listener who seeks to have a good understanding. Ask follow up questions. As practitioner, ensure both parties are actively listening to each other’s positions.

Reframe stories into needs. Let family members share what they want to share, but summarize and reframe the stories into needs. Blame about the past can be transformed into needs for the future.

Remember that you are not alone. Parties can try to ask for help from family members, friends, neighbours, clan members, Local Council Court, religious leaders etc. when they cannot reach agreements.

Involve neutral helpers. Family members should all feel confident that their helpers in the process are impartial and supporting fair solutions. As practitioner, give equal time and attention to each family member.

Take your time. It is important that all family members are given the time and space to share their underlying needs. Invest time in communicating. Summarize needs and acknowledge them before moving on.

Evaluate agreements. Families should ask each other about how they each feel about arrangements and make adjustments where necessary. All family members should be supportive of agreements.

Involve other providers/experts when needed. As a practitioner, assess the situation and your capacity and expertise. Engage other service providers or experts who can complement your services and help support the process.

Other suggested practices:

Consider the context of the conflict. Are there existing (clan) structures that can be used? Is there a need for a gender-specific helper? Are there any local norms that need to be considered?

Ensure there is privacy and confidentiality for all. Family members should feel safe in their privacy and confidentiality during the process.

Include all the affected family members. All family members, including children, could play a role in solving the problem as it affects them all.

Involve the community if helpful. Involve close family/community members who understand the situation and can help to solve the problem.

Encourage timely interventions. Ensure that interventions begin at an early stage in the conflict. Do not wait for the conflict to escalate.

Resources and Methodology

- Most plausible interventions

- PICO question

- Search strategy

- Assessment and grading of evidence

- Recommendation

- An assessment of the needs and objectives of both parties;

- An identification of the most appropriate interventions for the parties;

- Mediation;

- Arbitration, adjudication or another form of decision-making where mediation is not successful;

- Monitoring compliance and progress

The databases used are: HeinOnline, Westlaw, Wiley Online Library, JSTOR, Taylor & Francis, Peace Palace Library, ResearchGate, Bloomberg Law and LexisNexis Academic.

For this PICO question, keywords used in the search strategy are: mediation, litigation, fairness, process, outcome, agreement, divorce, family.

- Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Toward Another View of Legal Negotiation: The Structure of Problem Solving (1984)

- Carrie Menkel-Meadow The Lawyer as Problem Solver and Third-Party Neutral: Creativity and Nonpartisanship in Lawyering (1999)

- Jacqueline M. Nolan-Haley, Lawyers, Non-Lawyers and Mediation: Rethinking the Professional Monopoly from a Problem-Solving Perspective (2002)

- Jane C. Murphy, Revitalizing the Adversary System in Family Law (2010)

- Linda D. Elrod, Reforming the System to Protect Children in High Conflict Custody Cases (2001) ∙ Robert E. Emery et al., Child Custody Mediation and Litigation: Custody, Contact, and Coparenting 12 Years After Initial Dispute Resolution (2001)

- Peter Salem, The Emergence of Triage in Family Court Services: The Beginning of the End for Mandatory Mediation? (2009)

- Barbara A. Babb and Judith D. Moran, Substance Abuse, Families and Unified Family Courts: the Creation of a Caring Justice System (1999)

A problem-solving approach with a simple inventory of needs, interests, wants and goals of all parties will help develop (fair) solutions (Menkel-Meadow 1999, p. 797).

The problem-solving approach moves away from a positional articulation of problems to an interest-based articulation of problems. This approach opens up greater possibilities for developing broadened options and solutions that directly respond more to the parties’ underlying needs (Nolan-Haley, p. 249).

A distinction in low, medium or high conflict cases should be made, particularly in regard to custody cases. This way, appropriate time tracks can be created for different cases depending on complexity, need for services, and other factors (Elrod, p. 522). ‘Low conflict’ couples can avoid adversarial procedures.

In high conflict cases, couples should have access to mediation and arbitration [or another form of decision-making]. During this process, the parties attempt mediation. If they cannot reach an agreement, then a decision can be made [by a neutral third party] on their behalf (Elrod, p. 522). This way, fast solutions can be found to problematic matters where mediation is not effective.

In all cases, parenting plans should be monitored by a neutral third party, such as a therapist or mediator (Elrod, p. 533). These parenting plans should take into account the developmental needs of children (Elrod, p. 529).

Undesirable outcomes

A monitoring system of a final parenting plan is expensive and time-consuming (Elrod, p. 529). Problem-solving skills require an ability to identify and analyse underlying needs, expand resources, generate options, and help clients arrive at solutions that are truly responsive to their needs (Nolan-Haley, p. 249). Taking the problem-solving approach requires investment and training.

The adversarial system may exacerbate negative behaviours of parents who possess the financial resources for extended litigation and who believe the court will eventually prove them right (Elrod, p. 511).

According to social science research, children’s well-being following parental breakup depends on their parents’ (conflict) behaviour during and after the separation process. An adversarial approach creates more conflict (Elrod, p. 500), resulting in negative effects on children’s wellbeing.

Furthermore, in the context of custody issues, the adversarial system has proven to be poorly equipped to handle the complexities of interpersonal relations. It drives parents to find fault rather than cooperate (Elrod, p. 501). Accordingly, research shows that the adversarial approach is ill-suited to resolve disputes involving children (C. Murphy, p. 894).

Adversarial procedures in separation cases have been criticised for being expensive, time-consuming and divisive (Emery, p. 323). The adversarial system cuts all parties off from useful information such as facts, needs, interests, preferences and values. This can limit access to the crucial information that motivates people to resolve disputes (Menkel-Meadow 1999, p. 789).

Balance of outcomes

In determining whether taking a problem-solving approach is better than an adversarial approach for the well-being of parents and children during a separation process, the desirable and undesirable outcomes of both interventions must be considered.

Evidence suggests that taking the problem-solving approach helps to develop fair solutions, and opens greater possibilities to establish the parties’ underlying needs. On the other hand, investment and training might be needed.

Taking the adversarial approach might lead to more conflict behaviour and subsequently to negative effects on children’s well-being.

Accordingly, taking the problem-solving approach is recommended.

Recommendation

Taking into account the strength of evidence and the balance towards the desirable outcomes of the problem-solving approach, the following recommendation can be made: For people separating, the problem-solving approach is better than the adversarial approach for their well-being

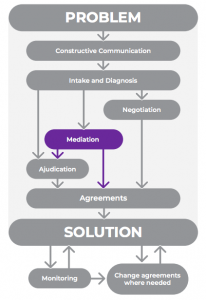

Mediate if the parties cannot agree themselves.

From the intake and diagnosis it becomes clear whether mediation is possible. A prerequisite is that both parties must be willing to meet together in one room.

During mediation two parties meet together with an impartial third party (a mediator). Together the parties identify, discuss and make agreements. The mediator provides support, but does not make decisions for them.

International research points out that mediation process and outcome are perceived to be fairer compared to litigation

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

How to get parties to mediate

Caucusing. As mediator, have separate talks with each party first. Explore their needs, with active listening and make them feel comfortable with the process.

Before starting mediation

Send invitations to both parties. Invitation letters should be given to both sides, clearly stating the goals, expectations and general overview of the mediation process. Since usually one of the parties brings the justice problem, there should be a clear message to invite the other party to come to the mediation.

Find a suitable mediator. The mediator should be impartial and promote a problem-solving approach. Both parties should feel comfortable with them. Factors such as age and gender should be considered if it affects the outcome of the process. Mediators should have sufficient training and experience, also in counseling.

Find a suitable location. Make sure the chosen venue is a welcoming and in a neutral setting that makes both sides feel comfortable.

Ensure accessibility. Both parties should be able to conduct the mediation in their own language and time, at an accessible location.

Ensure confidentiality. The mediator should ensure confidentiality of mediation.

During mediation

Explain the process. The mediator should take the time to clearly explain how the mediation will be conducted and what to expect.

Comfort. The mediator should make the parties feel comfortable with the mediator. The parties should trust the mediator.

Respectful communication. Ensure there is mutual respect between the parties and towards the mediator. Both parties should always speak calmly, not raising voices or making accusations.

Promote active listening. The mediator should ensure that both parties are listening to the other’s views. ∙ Focus on needs/interests. Bring the focus of the conversation towards identifying needs, not blaming others.

Give it time and space. The mediator should ensure that both parties are able to present their own needs and views at their own pace. Do not leave anything unsaid.

After mediation

Let the parties own the decision. Mediators should not impose a decision. The family members should be in full agreement.

Formalize agreement. An agreement should be clearly written and signed by both parties. Both parties should understand that this is a binding agreement and that there are certain consequences attached to that.

Other suggested practices

Make the parties feel welcome. As mediator, politely welcome both parties and make them feel at ease. The mediator should provide a “homely” environment.

Always look for win-win situations. Work towards agreements that make all parties happy.

Involvement of children. The views and needs of children should be taken into consideration. Sensitive topics, such as bedroom issues between the couple should be handled away from the presence of children

Resources and Methodology

- Most plausible interventions

- PICO question

- Search strategy

- Assessment and grading of evidence

- Recommendation

- Lori Anne Shaw, Divorce Mediation Outcome Research: A Meta-Analysis (2006)

- Robert Emery, Divorce Mediation (1986)

- Linda D. Elrod, Reforming the System to Protect Children in High Conflict Custody Cases (2001)

- Joan B. Kelly, Family Mediation Research: Is There Empirical Support for the Field? (An Update) (2014)

Parents should communicate and cooperate with each other

They should try to interact, communicate and cooperate with each other. Communication is essential in order to transform and adapt to a new situation.

Parents should decide together on how often they interact or communicate about their children’s needs. Parents can discuss child-related issues in person on arranged times.

Examples of items to be discussed are:

- The children’s medical needs and educational needs;

- The children’s academic accomplishments and progress;

- The children’s personal problems;

- Special events;

- Personal problems that the children experience;

- Major decisions affecting children;

- Finances in regard to children;

- Problems in parenting;

- Decisions regarding children’s lives;

- Children’s adjustment.

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

Communicate at agreed moments. Parents should make a plan to speak about their problems face-to-face at specific moments, rather than reacting emotionally to things as they happen.

Use positive (body) language. Parents should not be aggressive or defensive in the way they communicate. They should be open and honest about their emotions but do it in a constructive way.

Show respect. The parties should make each other feel respected in order to be able to effectively communicate.

Other suggested practices:

Where appropriate, make sure there is eye-contact – In some cultures, eye-contact encourages truth and understanding

Resources and Methodology

During the orientation process of the available literature, we were able to identify the following interventions:

- Mutual constructive communication

- Demand/withdraw communication

- Mutual avoidance

Mutual constructive communication is interactive, involves constructive problem-solving and focuses on avoiding conflict (Handbook, p. 203). Both parties try to engage in a mutual adaptive discussion (Diamond, p. 202). Demand/withdraw communication involves a pattern where one partner pursues more closeness and contact, while the other partner desires more distance and responds by withdrawing and avoiding (Handbook, p. 203). Mutual avoidance is typified by both partners avoiding communicating as much as possible (Handbook, p. 203). For the purpose of this topic, ‘mutual constructive communication’ will be compared with both ‘mutual avoidance’ and ‘demand/withdraw communication’ simultaneously

The main source used for this particular subject is The Handbook of Family Communication, edited by Anita L. Vangelisi. Three chapters have been used in particular, these being:

Chapter 9, Communication in Divorced and Single-Parent Families, Julia M. Lewis, Judith S. Wallerstein and Linda Johnson-Reitz

Chapter 13, Mothers and Fathers Parenting Together, William J. Doherty and John M. Beaton

Chapter 19, Communication, ‘Conflict and the Quality of Family Relationships’, Alan Sillars, Daniel J. Canary and Melissa Tafoya

Other sources used:

Diamond and Brimhall, Communication During Conflict: Differences Between Individuals in First and Second Marriages (2013)

Guy Bodemann, Andrea Kaiser, Kurt Hahlweg and Gabriele Fehm-Wolfsdorf, Communication patterns during marital conflict: A cross-cultural replication (1998)

The Handbook of Family Communication presents an analysis of cutting-edge research and theory on family interaction. It integrates perspectives of researchers and practitioners. Chapter 9 is mostly based on large-scale observational studies, and a few meta-analyses that help to understand what happens when families separate. Chapter 13 and 19 mostly rely on observational studies. Evidence can be regarded as being low to moderate

Desirable outcomes

Communication between parents becomes more difficult and energy consuming after separation. Unexpected and overwhelming demands after separation results in less communication by the parents. Parents will need to communicate more often and effectively, so that the parenting styles of both parents are consistent (Handbook, p. 204). Research shows that mutual constructive communication is generally designated as the healthiest, most functional interactive pattern. Separated parents must be willing to interact, communicate and cooperate with each other regarding child-related issues, despite any feelings of rejection, remorse, bitterness, or anger. This is because parental responsibilities after separation continue to exist, and communication is essential to transform and adapt to accommodate to parents’ new roles (Handbook, p. 204).

The ability of separated parents to co-parent together, communicate about their children, to cooperate to set limits, to problem solve effectively and to provide consistent positive affective messages has a major influence on the ability of children to adjust after separation (Handbook, p. 205).

Undesirable outcomes

Mutual avoidance communication prevents the airing of thoughts and feelings surrounding relationship problems and impedes movement towards resolution (Diamond, p. 199).

Both avoidance and demand/withdrawal communication are correlated with lower relationship satisfaction (Bodenmann, p. 354).

Balance of outcomes

between parents is more effective than mutual avoidance, for their well-being, the desirable and undesirable outcomes of both interventions must be considered.

The literature suggests that mutual constructive communication between parents is in the interest of the child. On the other hand, mutual avoidance and demand/withdrawal communication are correlated with lower relationship satisfaction and a lack of ability to move towards a resolution.

The balance is clearly towards the desired outcomes of mutual constructive communication.

Recommendation

Taking into account the balance towards the desired outcomes, the effect on children’s well-being and the strength of the evidence, we make the following recommendation: For the parents and children, mutual constructive communication between parents is effective than mutual avoidance, for their well-being

Parents should love and nurture their child, at the same time they are demanding and in control

Parents should have high levels of control and maturity demands over their children, combined with high levels of nurturance. This means that they show warmth, support, effective monitoring, control, discipline, positive discussion and responsiveness to their children’s needs. Parents rely on positive sanctions to gain their child’s compliance and encourage their child to express himself when he disagrees. This is referred to as ‘authoritative parenting’. According to international research, authoritative parenting plays an important role in children’s academic performance.

There are 3 types of parenting that have been shown to have different effects on the wellbeing of children:

Authoritative parenting – Where parents have high demands from their children but are also loving and nurturing their emotional needs. This is seen as the most effective type of parenting.

Permissive parenting – Where parents show love and care towards their children, but not give enough direction and guidance.

Authoritarian parenting – Parents are strict and demanding but are not supportive enough of the children’s emotional needs.

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

Ensure child-friendly disciplining. Offer the child appropriate measures in disciplining actions. Avoid abusive actions that can harm a child.

Both parents should participate in education. Both parents should be involved with the school education of the child. They should both be aware of their situation at school and have contact with teachers, provide support with homework etc.

Parents shouldn’t favour children. Both girls and boys should be equally loved and supported by both parents.

Make sure that girls and boys are treated equally. There should be no discrimination in assigning resources and responsibilities to them, or in reprimanding them.

Take time to understand the needs of children. Parents should make sure they understand their children’s needs and provide for them.

Other suggested practices:

Make sure children are consulted about their education. Make sure they are safe and comfortable in their schools.

Try to learn more about parenting skills. Ask others to find out if there are resources that can help you to learn about good parenting. These could include radio broadcasts, books or gatherings

Resources and Methodology

During the orientation process of the available literature, we were able to identify three interventions, these being:

- Authoritative parenting

- Authoritarian parenting

- Permissive parenting

Authoritative parenting is characterised by having high levels of control and maturity demands, combined with high levels of nurturance. These parents rely more on positive than negative sanctions to gain their child’s compliance and encourage their child to express himself/herself when the child disagrees (Handbook, p. 452).

Authoritarian parents display high levels of control along with low levels of clarity and nurturance. These parents rely on power-assertive forms of discipline. They are less likely than authoritative parents to provide reasons when attempting to alter their child’s behaviour and discourage expressions of the child’s disagreement (Handbook, p. 452).

Permissive parenting is characterised by parents who display low levels of control and maturity demands, combined with higher levels of nurturance. They are less likely than authoritative parents to enforce rules or structure for their child’s activities (Handbook, p. 452).

For the purpose of this PICO question, we compare authoritative parenting with the two other forms of parenting, because authoritative parenting shows a high level of demandingness and nurturance, while the other two parenting styles either have a low level of demandingness or nurturance (Handbook, p. 452)

The four main sources used for this particular subject are:

- Sanford M. Dornbusch, Philip L. Ritter, P. Herbert Leiderman, Donald F. Roberts and Michael J. Fraleigh, The Relation of Parenting Style to Adolescent School Performance (1987)

- Fletcher, Steinberg and Sellers, Adolescents’ well-being as a function of perceived interparental consistency (1999)

- The Handbook of Family Communication, edited by Anita L. Vangelisi, Chapters 9, 20 and 27 (2004)

- Erlanger A. Turner, Megan Chandler and Robbert W. Heffer, The Influence of Parenting Styles, Achievement Motivation and Self-Efficacy on Academic Performance in College Students (2009)

- Linda Nielsen, Shared Parenting After Divorce: A Review of Shared Residential Parenting Research” (2011)

These sources are largely based on an RCT and several observational studies. According to the HiiL Methodology: Assessment of Evidence and Recommendations, the strength of this evidence is classified as ‘low’ to ‘moderate’.

Desirable outcomes

For the child’s interest, authoritative parenting by both parents with warmth, support, effective monitoring, control, discipline, positive discussion and responsiveness to children’s needs is essential (Handbook, p. 204). Studies indicate the following:

Children of separated parents benefit the most when their father is actively engaged in their lives across a wide range of daily activities and when he has an authoritative rather than permissive or authoritarian parenting style (Nielsen, p. 591)

Children are less depressed, were less aggressive and had higher self-esteem when both parents are authoritative (Nielsen, p. 599)

Children with at least one authoritative parent have been linked to better academic competence and higher grades (Fletcher, Steinberg and Sellers p. and Dornbusch et al., p. 1256)

Children from parents applying an authoritative parenting style do better at school compared to the other parenting styles (Dornbusch et al., p. 1256).

A consistent and authoritative parenting style is effective (Afifi, p. 751). Parenting characteristics such as supportiveness and warmth continue to play an important role in influencing a student’s academic performance (Turner et al., p. 343).

Authoritative parenting is associated with lower levels of substance abuse for children (Handbook, p. 616)

Parenting characteristics such as supportiveness and warmth continue to play an important role in influencing a student’s academic performance (Turner et al., p. 343).

Undesirable outcomes

Children from families applying authoritarian or permissive parenting tend to do less well at school compared to the authoritative parenting style (Dornbusch et al., p. 1256 and Turner, p. 338).

Parenting styles with controlling contexts (such as the authoritarian parenting style) diminish autonomous motivation and enhance controlled motivation (Turner, p. 339). In other words, the authoritarian parenting style limits the ability of children to make their own choices and control their own life.

Balance of outcomes

In determining whether the authoritative parenting style is more effective than the authoritarian and permissive parenting styles, the desirable and undesirable outcomes of both interventions must be considered.

The literature suggests that, regarding academic achievement, the authoritative parenting style is in the interest of the child while the authoritarian and permissive parenting styles are not.

The balance of outcomes is in favour of an authoritarian parenting style.

Recommendation

Taking into account the balance of outcomes, the high effect on children’s well-being and the strength of the evidence, we make the following strong recommendation: For children, authoritative parenting is more effective than other forms of parenting for their well-being

0 Comments