The mediator should be outcome-focused

He or she steers the process; through posing solution-focused questions, he or she encourages the clients to look ahead to their desired future situation and how they can achieve this outcome. It revolves around the outcome that the clients want to achieve. Solution-focused mediators will ask “What would you prefer instead of the conflict?”, defined in positive, realistic and concrete terms.

What practitioners say

Be aware of different mediation providers. Many formal and informal justice providers, such as police and cultural leaders offer mediation services. Some of them are not trained mediators. There are specialized and trained mediators available, to whom can be referred to.

Be aware of different mediation types. The main types of mediation are transformative, facilitative, and evaluative.

- Evaluative mediation is the style of mediation where the mediator exerts the most control throughout the mediation, and is the most vocal about the positions and offers of the parties.

- In facilitative mediation, the mediator will control the procedure of the mediation, but the parties control the outcome.

- Transformative mediation seeks to transform the conflict by empowering the parties to agree. The transformative mediator is only in the room to call attention to the needs, interests, values and points of view of the parties.

Be aware of the costs of mediation. When parties decide to mediate, the parties need to pay. In government-initiated mediation, the parties do not directly have to pay. Parties do not have to pay the police for reporting and offered mediation.

Conduct gender and power analyses. The dynamics in families will need to be identified. Power imbalance refers to decision-making and access to resources within a family. Who provides income? Who takes care of the children? Be careful, bringing up the topic of power balance can escalate the conflict. Moderate the words, use a different term than balance (for example: position of the parties, or personal standing of the parties). Economic status does not always defines power. Rather discuss negotiation ability

.

Resources and Methodology

This page focuses on specific meditation techniques that can be applied by mediators, regardless the mediation style. James Wall identified 100 mediation techniques (Druckmann and Wall, p. 1915). We compare two techniques, leaving much room for further research on other mediation techniques.

One technique that can be applied by mediators is formulating questions that seek to get clients to make suggestions about solutions. These questions are referred to as solution-focused questions, which originates from solution-focused brief therapy (Stokoe and Sikveland). The mediator is outcome-focused. The mediator tends to steer the process; through posing solution focused questions, he or she encourages the clients to look ahead to their desired future situation and how they can achieve this outcome. It revolves around the outcome that the clients want to achieve (Bannink, p. 176). Solution-focused mediators will ask “What would you prefer instead of the conflict?”, defined in positive, realistic and concrete terms (Bannink, p. 177).

Another technique for mediators is to formulate problem-focused questions. Problem-focused questions are focused on the history of the conflict (Bannink, p. 175-176). According to the problem-focused model the mediator first needs to explore and analyze the problem. Clients describe the problem and then negotiate an agreement that satisfies the needs of all involved. Mediators facilitate negotiation and are focussed on the process rather than on outcomes

Problem-focused questions Solution-focused questions Solution-focused conversations have a positive effect in less time and satisfy the client’s need for autonomy more than problem-focused conversations.

The solution-focused model has proved to be applicable in all situations where there is the possibility of a conversation between client and professional (Bannink, p. 174).

Applying solution-focused questions results in increased self-efficacy and other positive effects.

According to a randomized study comparing solution-focused and problem-focused questions in the field of coaching], the solution-focused approach significantly increased positive affect, decreased negative affect and increased self-efficacy. Solution-focused questions generated significantly more action steps to help people to reach their goals (Grant, p. 88).

The solution-focused approach ensures a continuous evaluation of the mediation process.

By asking scaling questions throughout the mediation process and by asking at the beginning of each conversation “What is better?”, evaluation of mediation is taking place continuously (Bannink, p. 180). [This could enhance the quality of mediation and perhaps quality of solutions].

Undesirable outcomes Problem-focused questions Solution-focused questions Problem-focused questions can slow down the process of finding a solution.

If the problem or conflict and its possible causes are studied, a vicious circle may be created with ever-increasing problems. This atmosphere becomes loaded with problems, bringing with it the danger of losing sight of the solution (Bannink, p. 175).

Applying problem-focused questions can result in a negative atmosphere.

Conversations about the clients’ positions and a familiarization with the history of the conflict are both deemed not only unnecessary but even undesired, due to their negative influence on the atmosphere during the conversation and the unnecessary prolongation of the mediation (Bannink, p. 176). Applying solution-focused questions may result in solutions that are not owned by the parties in conflict.

Clients want mediators to provide solutions and not leave it for them to ‘sort out differences’. The challenge here can be found in formulations and solution-focused, (or rather solution-proposing) questions. Solutions are the work of mediation, but they are not necessarily the work of clients (Stokoe and Sikveland). [In order for mediators to avoid proposing solutions to their clients, they should be careful in phrasing solution-focused questions].

Balance of outcomes Asking solution-focused questions by a mediator positively affects people’s wellbeing. Mediators should be careful in formulating these questions.

Problem-focused questions on the other hand are not associated with increasement of well-being. In fact, research suggests that applying problem-focused questions may result in a slower resolution process and a negative atmosphere between parties.

The desirable outcomes of solution-focused questions outweigh those of problem-solving questions. Therefore, applying solution-focused questions is preferred.

Recommendation Taking into account the balance of outcomes, the effect on neighbours’ well-being, and the quality and consistency of the evidence, we make the following recommendation: For neighbours in conflict, asking solution-focused questions by the mediator is more effective than asking problem-focused questions, for their well-being.

Apply the problem-solving approach

For a practitioner, it can be difficult to encourage families to work together and find solutions. Family conflicts often lead to tense and emotional situations. But there are effective methods to reach agreements.

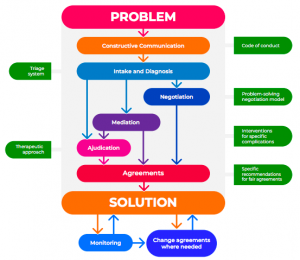

The problem-solving approach focuses on finding solutions for the parties’ underlying needs and objectives. The first step for the parties and their helpers is to assess these needs and objectives. Then, the most appropriate interventions are identified, followed by negotiation. Remaining issues are solved by mediation, and if necessary, by adjudication. Compliance and effectiveness of the agreed upon solutions are monitored.

International research shows that taking the problem-solving approach contributes to reaching fair solutions

..

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

Work towards building agreements based on shared understandings. All family members and their helpers should feel a shared responsibility to focus on finding a solution together.

Listen to needs of the other person. Parties should try to listen to and understand the other person. They should ask questions if there is unclarity about what the other person needs. When responding, parties should try to contribute to a solution and not just focus on the problem.

Identify the needs of each family member. What does each family member need in order to be able to move on?

Actively listen to what is being said. As a party, be an attentive and active listener who seeks to have a good understanding. Ask follow up questions. As practitioner, ensure both parties are actively listening to each other’s positions.

Reframe stories into needs. Let family members share what they want to share, but summarize and reframe the stories into needs. Blame about the past can be transformed into needs for the future.

Remember that you are not alone. Parties can try to ask for help from family members, friends, neighbours, clan members, Local Council Court, religious leaders etc. when they cannot reach agreements.

Involve neutral helpers. Family members should all feel confident that their helpers in the process are impartial and supporting fair solutions. As practitioner, give equal time and attention to each family member.

Take your time. It is important that all family members are given the time and space to share their underlying needs. Invest time in communicating. Summarize needs and acknowledge them before moving on.

Evaluate agreements. Families should ask each other about how they each feel about arrangements and make adjustments where necessary. All family members should be supportive of agreements.

Involve other providers/experts when needed. As a practitioner, assess the situation and your capacity and expertise. Engage other service providers or experts who can complement your services and help support the process.

Other suggested practices:

Consider the context of the conflict. Are there existing (clan) structures that can be used? Is there a need for a gender-specific helper? Are there any local norms that need to be considered?

Ensure there is privacy and confidentiality for all. Family members should feel safe in their privacy and confidentiality during the process.

Include all the affected family members. All family members, including children, could play a role in solving the problem as it affects them all.

Involve the community if helpful. Involve close family/community members who understand the situation and can help to solve the problem.

Encourage timely interventions. Ensure that interventions begin at an early stage in the conflict. Do not wait for the conflict to escalate

Resources and Methodology

- An assessment of the needs and objectives of both parties;

- An identification of the most appropriate interventions for the parties;

- Mediation;

- Arbitration, adjudication or another form of decision-making where mediation is not successful;

- Monitoring compliance and progress

- Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Toward Another View of Legal Negotiation: The Structure of Problem Solving (1984)

- Carrie Menkel-Meadow The Lawyer as Problem Solver and Third-Party Neutral: Creativity and Nonpartisanship in Lawyering (1999)

- Jacqueline M. Nolan-Haley, Lawyers, Non-Lawyers and Mediation: Rethinking the Professional Monopoly from a Problem-Solving Perspective (2002)

- Jane C. Murphy, Revitalizing the Adversary System in Family Law (2010)

- Linda D. Elrod, Reforming the System to Protect Children in High Conflict Custody Cases (2001) ∙ Robert E. Emery et al., Child Custody Mediation and Litigation: Custody, Contact, and Coparenting 12 Years After Initial Dispute Resolution (2001)

- Peter Salem, The Emergence of Triage in Family Court Services: The Beginning of the End for Mandatory Mediation? (2009)

- Barbara A. Babb and Judith D. Moran, Substance Abuse, Families and Unified Family Courts: the Creation of a Caring Justice System (1999)

Mediate if the parties cannot agree themselves.

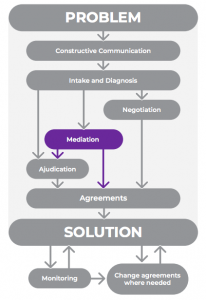

From the intake and diagnosis it becomes clear whether mediation is possible. A prerequisite is that both parties must be willing to meet together in one room.

During mediation two parties meet together with an impartial third party (a mediator). Together the parties identify, discuss and make agreements. The mediator provides support, but does not make decisions for them.

International research points out that mediation process and outcome are perceived to be fairer compared to litigation

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

How to get parties to mediate

Caucusing. As mediator, have separate talks with each party first. Explore their needs, with active listening and make them feel comfortable with the process.

Before starting mediation

Send invitations to both parties. Invitation letters should be given to both sides, clearly stating the goals, expectations and general overview of the mediation process. Since usually one of the parties brings the justice problem, there should be a clear message to invite the other party to come to the mediation.

Find a suitable mediator. The mediator should be impartial and promote a problem-solving approach. Both parties should feel comfortable with them. Factors such as age and gender should be considered if it affects the outcome of the process. Mediators should have sufficient training and experience, also in counseling.

Find a suitable location. Make sure the chosen venue is a welcoming and in a neutral setting that makes both sides feel comfortable.

Ensure accessibility. Both parties should be able to conduct the mediation in their own language and time, at an accessible location.

Ensure confidentiality. The mediator should ensure confidentiality of mediation.

During mediation

Explain the process. The mediator should take the time to clearly explain how the mediation will be conducted and what to expect.

Comfort. The mediator should make the parties feel comfortable with the mediator. The parties should trust the mediator.

Respectful communication. Ensure there is mutual respect between the parties and towards the mediator. Both parties should always speak calmly, not raising voices or making accusations.

Promote active listening. The mediator should ensure that both parties are listening to the other’s views. ∙ Focus on needs/interests. Bring the focus of the conversation towards identifying needs, not blaming others.

Give it time and space. The mediator should ensure that both parties are able to present their own needs and views at their own pace. Do not leave anything unsaid.

After mediation

Let the parties own the decision. Mediators should not impose a decision. The family members should be in full agreement.

Formalize agreement. An agreement should be clearly written and signed by both parties. Both parties should understand that this is a binding agreement and that there are certain consequences attached to that.

Other suggested practices

Make the parties feel welcome. As mediator, politely welcome both parties and make them feel at ease. The mediator should provide a “homely” environment.

Always look for win-win situations. Work towards agreements that make all parties happy.

Involvement of children. The views and needs of children should be taken into consideration. Sensitive topics, such as bedroom issues between the couple should be handled away from the presence of children

Resources and Methodology

Mediation is a commonly used intervention to resolve family disputes (Emery, p. 472 and Shaw, p. 447). Typically, the parties meet together with an impartial third party in order to identify, discuss and resolve their disputes (Emery, p. 472). The third party merely facilitates the process and does not make a binding decision for the disputants; unlike in a litigation process. In essence, the disputants negotiate their own agreement.

There is evidence available regarding user satisfaction with mediation and litigation processes and outcomes, children’s wellbeing and other factors (such as costs and time benefits).

Mediation is only considered an option for disputants who are willing to meet together. Mediation is most effective if there is a possibility to receive quick decisions from a third party

- Lori Anne Shaw, Divorce Mediation Outcome Research: A Meta-Analysis (2006)

- Robert Emery, Divorce Mediation (1986)

- Linda D. Elrod, Reforming the System to Protect Children in High Conflict Custody Cases (2001)

- Joan B. Kelly, Family Mediation Research: Is There Empirical Support for the Field? (An Update) (2014)

A neutral decision-maker can help make decisions where needed

It is possible that the parties cannot reach agreement on all matters after negotiation and mediation. In that case, they need a neutral third party to get there. A problem-solving judge attempts to understand and address the underlying problem. The judge facilitates and creates the best environment for the parties to decide on agreements.

Such therapeutic approach to adjudication ensures a more comprehensive solution tailored to the legal, personal, emotional and social needs of the family members.

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

Ensure neutrality. The decision-maker should be a neutral third party.

Explain the process. The decision-maker should take the time to clearly explain how the decision-making process works.

Communicate respectfully. Parties should ensure there is mutual respect towards each other and the decision-maker. Both parties should always speak calmly, not raising voices or making accusations.

Focus on needs/interests. Bring the focus of the decision towards the needs, not blaming others.

Formalize agreements. An agreement should be clearly written and signed by both parties. Both parties should understand that this is a binding agreement and that there are certain consequences attached to that

Resources and Methodology

- An adversarial (or traditional) approach in a family context (where the judge only focuses on the parties and their legal dispute)

- A therapeutic approach in a family context, such as unified family courts (where the judge focuses on the family as a social system), characterized by a problem-solving judge

The adversarial approach is formal and only takes place within court. The main aim of taking an adversarial approach is truth-finding. It is a monopoly approach (instead of multidisciplinary) and its basic premises are post-conflict solutions, conflict and dispute resolution (Freiberg, p. 3). Taking an adversarial approach generally results in more claims of the parties (Miller and Sarat, p. 542) compared to a non-adversarial approach.

The goal of the therapeutic approach is to maximize the positive effects of legal interventions on the social, emotional and psychological functioning of individual families. The problem-solving judge is a critical actor in this endeavor. Rather than solving discrete legal issues [such as in the adversarial approach], the problem-solving judge attempts to understand and address the underlying problem and emotional issues and helps participants to effectively deal with the problem (Boldt and Singer, p. 91 and 95-96). The problem-solving judge embraces collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches. He motivates individuals to accept needed services (Boldt and Singer, p. 96). All legal actors involved in the therapeutic approach to separation are therapeutic agents, considering the mental health and psychological wellbeing of the people they encounter in the legal setting (Babb and Moran, p. 1063).

In some jurisdictions the primary role of family courts has shifted from [adversarial] adjudication of disputes to therapeutic approach (Lande, p. 431). For example, the unified family court system in the United States.

Unified family court systems are characterized by a holistic approach to family legal problems, an emphasis on problem-solving and alternative dispute resolution and the provision and coordination of a comprehensive range of court-connected family services (Boldt and Singer, p. 91). All matters involving the same family should be handled by one single judge (or judicial team) (Boldt and Singer, p. 96).

- Richard E. Miller and Austin Sarat, Grievances, Claims and Disputes: assessing the Adversary Culture (1980)

- Nancy Ver Steegh, Yes, No and Maybe: Informed Decision Making About Divorce Mediation in the Presence of Domestic Violence (2003)

- Barbara A. Babb and Judith D. Moran, Substance Abuse, Families and Unified Family Courts: the Creation of a Caring Justice System (1999)

- Jana B. Singer, Dispute Resolution and the Post-divorce Family: Implications of a Paradigm Shift (2009) ∙ Andrew Schepard, Parental Conflict Prevention Programs and the Unified Family Court: A Public Health Perspective (1998)

- Peter Salem, The Emergence of Triage in Family Court Services: The Beginning of the End For Mandatory Mediation (2009)

- John Lande, The Revolution in Family Law Dispute Resolution (2012) ∙ Richard Boldt and Jana Singer, Juristocracy in the Trenches: Problem-solving Judges and Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Drug Treatment Courts and Unified Family Courts (2006)

- Bruce J. Winick, Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Problem Solving Courts (2003)

- Arie Freiberg, Non-adversarial approaches to criminal justice (2007)

The family first conducts an intake with the practitioner to find out what their needs are

Parties cannot always find solutions themselves.

They need help from a third party. In order to reach agreements, the parties start by conducting an intake. Together with the practitioner they find out what their needs are.

The practitioner provides a diagnosis, based on the intake

Based on the intake outcomes, the parties receive a diagnosis from a trained professional. The practitioner prescribes the most appropriate intervention, for example mediation or adjudication.

According to research, the intake and diagnosis are essential for the parties to receive the best help possible

.

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

Keep records. As practitioner, make sure intakes, diagnoses and further steps are recorded. This will make it easier to ensure agreements are respected and evaluated.

Equal participation. As practitioner, let both parties participate actively in the diagnosis. Both sides should get equal attention and be equally involved in the process.

Keep the end in mind. Both parties should create a list of desired outcomes and then work backwards.

Other suggested practices:

Define clearly what the conflict is about. The parties should clearly define what the grievance is about before the intake process

Resources and Methodology

The role of family courts is shifting from one of only adjudicating cases, to planning and managing them (Lande, p. 432). In particular, there has been a movement towards a single judge and [interdisciplinary] professional team that would deal with all issues affecting a particular family, including separation (Lande, p. 432). [Integrated] family courts that actively manage referrals to various services use two alternative systems: the ‘tiered’ and ‘triage’ system (Lande, p. 432).

A tiered system of solving family disputes starts with the least intrusive and least time consuming service and, if the dispute is not resolved, proceeds to the next available process. The next steps are more intrusive and directive than the preceding one. Typically, parents therefore start mediation before adjudication (Salem, p. 371).

In a triage system, the most appropriate services are identified at the beginning (Salem, p. 372). Parents may complete an initial interview, and agency representatives help them to identify the service they believe will best meet the needs of the family (Salem, p. 380). The process may involve screening, development of a plan for family services, appointment of a case manager, development of a parenting plan and periodic court review (Lande, p. 432).

We compare the triage system with the tiered system

- Peter Salem, The Emergence of Triage in Family Court Services: The Beginning of the End For Mandatory Mediation (2009)

- John Lande, The Revolution in Family Law Dispute Resolution (2012)

- Nancy Ver Steegh, Family Court Reform and ADR: Shifting Values and Expectations Transform the Divorce Process (2008)

Desirable outcomes

Desirable outcomes Prior to participating in the adversarial litigation process, parents should have the opportunity to participate in mediation, so that they may collaborate with one another and create their own agreement (Salem, p. 274). If mediation does not result in an agreement, other processes remain available (Salem, p. 276).

Some courts in the US have adopted the Differentiated Case management system as a way to more efficiently match families with processes and services. A case goes through triage and a service plan is created for the family. Unlike linear service delivery models [i.e. a tiered system], high-conflict families proceed directly to the programs and services most likely to be successful for them in developing a parenting plan or having parenting arrangements decided for them. Court systems have expanded their role to include activities such as screening, assessment, creation of service plans and referral to community resources (Ver Steegh, p. 668-669). A system that identifies the best match between a family and available service, will provide the most appropriate services, resulting in more efficient use of resources and reducing the burden on families (Salem, p. 381).

Undesirable outcomes If parents are referred to mediation and do not settle, they are often required to participate in additional, and increasingly intrusive processes [such as adjudication] until matters are resolved. When more services are necessary, more money and time is demanded of the parties. This raises frustration, as expressed by members of a focus group in Wisconsin, United States (Salem, p. 382). Some argue that triage will result in some disputing parents missing out on mediation and its important benefits. They say that there is no evidence that one can accurately predict who will succeed in mediation and who won’t, and so suggest that mediation should be mandatory for virtually all parents disputing child custody matters (Salem, p. 372). Balance of outcomes In determining whether a triage approach to separation is better than the tiered approach for the well-being of parents and children during a separation process, the desirable and undesirable outcomes of both interventions must be considered. From the above evidence, the benefits of a triage approach outweigh those of a tiered approach. In particular because the triage system limits frustration of the people compared to the tiered system. Unlike the tiered model, the triage system ensures that the parties make use of the most appropriate intervention. Recommendation Taking into account the strength of evidence and the clear balance towards the desirable outcomes of a triage model, the following recommendation can be made: For people separating, the triage model is better than the tiered model for their well-being.